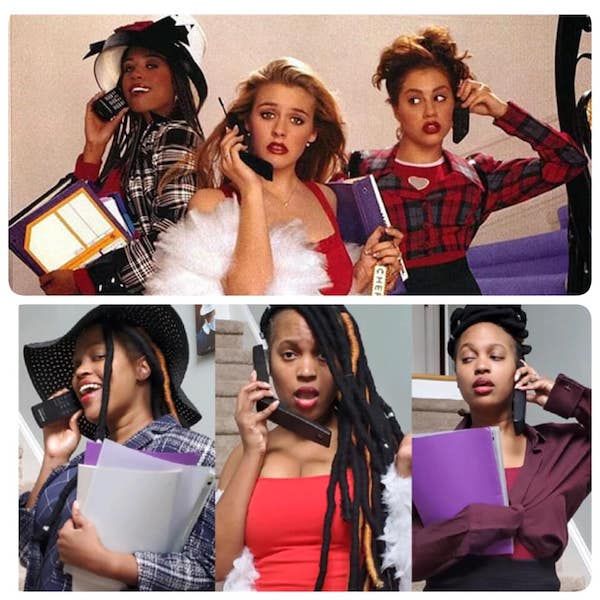

Undoubtedly, you’re shaking your head right now and calling me weird. While you’re correct about that, you’re wrong if you don’t think Austen is funny. Readers and literary scholars alike laud her work for its biting irony and her constant roasting of the British gentry. Of course, humor was different in the 18th century. Consequently, it might be challenging for a modern reader to catch her nuanced jokes. Allow me, therefore, to elucidate. Jane Austen lived from 1775 to 1817 in Hampshire, England. Austen never married, instead focusing on familial relationships and her writing. For the times she lived in, not marrying was remarkable. Her so-called spinsterhood gave her fodder for writing about women bent on finding a “good” husband. Rumor even has it that she agreed to marry in 1802, but changed her mind the next morning. What. An. Icon. Austen published four novels during her short life: Sense and Sensibility (1811), Pride and Prejudice (1813), Mansfield Park (1814), and Emma (1815). My personal favorite, Persuasion, was published posthumously along with my least favorite, Northanger Abbey, in 1817. One of her nephews published her short epistolary novel, Lady Susan, in 1871. Despite this comparatively short list of published works, Austen’s legacy has endured for centuries. Her books have been adapted for the stage, television, and big screen dozens of times. Additionally, there are countless retellings and reimagining based on her books. (My personal favorite is Clueless, which is a modern take on Emma.) I contend that one of the reasons her work endures is because of its humor. We humans enjoy laughing at ourselves and others. As Austen says in Pride and Prejudice, “For what do we live, but to make sport for our neighbors, and laugh at them in our turn?”

Austen Makes Fun of Marriage and the Patriarchy

Pride and Prejudice introduces us to the Bennet family and their ridiculous matriarch, Mrs. Bennet. She is described as “a woman of mean understanding, little information, and uncertain temper. When she was discontented, she fancied herself nervous. The business of her life was to get her daughters married; its solace was visiting and news.” All Mrs. Bennet wants in life is to see her five daughters “well married,” but she not only hinders their success at every turn, but doesn’t even seem to understand what “well married” means. She’s equally joyful when Lydia marries the villainous Mr. Wickham as she is when Jane and Elizabeth make matches with rich, good men. Of course, Mrs. Bennet’s ceaseless quest for matrimony wouldn’t be so necessary if it weren’t for the patriarchal society she lived in. Because she’d birthed five daughters and no son, her family’s estate was entailed away from her girls and would be inherited by a male cousin. Since she and her husband had barely lived within their means, they had nothing to give their children. Austen even made sure to point out the stupidity of the entail by contrasting the Bennet’s situation with that of Lady Catherine’s family. Lady Catherine and her husband’s estate would belong to their only daughter. There are so many moments of absolute foolishness out of Mrs. Bennet. She is a hypochondriac who takes to her bed when Lydia runs away, but pops out of bed ready to party the moment she finds out Wickham has been prevailed upon to marry her wayward child. She is constantly saying the wrong thing, getting drunk, and gossiping. Most telling, however, is that despite all of her fervor for marriage. Mrs. Bennet is unhappy in her own. Her husband doesn’t love or respect her and delights in laughing at her in front of her children. Like her neighbor, Charlotte Lucas, Mrs. Bennet rests all her matrimonial bliss on her children and managing her home. (Of course, Charlotte knew her husband was a fool when she married him, which is also hilarious.)

Austen Roasts the Rich and Ranked

Since I mentioned Lady Catherine de Bourgh, I’ll start with her as an example of Austen’s relentless roasting of the rich and ranked. In Austen’s time, your birth, land ownership, and titles were very important to your status in society. They determined who you could marry or even speak to. Gentlemen and ladies were supposed to be well-bred and followed an intricate set of rules of politeness. However, when Elizabeth Bennet meets Darcy’s rich aunt, she is not what she should be. Rather than a model of good breeding, Lady Catherine is nosy, loud, clueless, and officious. Her sickly and moody daughter is just a bad, though quieter. Austen shows us this through hilarious scenes where Mr. Collins grovels and flatters, while Lady Catherine drones on about how great she and her daughter are. It doesn’t even matter if they have any talent or knowledge to back up her assertions. For example, after yelling across the room to find out what two other characters were talking about, Lady Catherine said this: Lady Catherine is one of many examples of a rich and/or highly ranked character who turns out to be just the worst. In Persuasion, every member of the Elliot family besides Anne is obsessed with their rank. They’re all constantly offended if they’re not treated with the honors due to a baronet and his daughters. They’re vain and petty and constantly seeking compliments and attention. Lady Catherine de Bourgh in Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen Much like Lady Catherine has to learn to accept Darcy and Elizabeth rejecting her judgment and authority, the elder Elliots get their comeuppance. Sir Walter and Elizabeth Elliot lose their lackey to another Elliot with more to offer. They’re somewhat comforted by having grander relations to spend time with. However, they soon learn (in Austen’s words) “to flatter and follow others, without being flattered and followed in turn, is but a state of half enjoyment.”

Austen Just Throwing Shade

To close, here are some of my favorite shady or sassy quotes that demonstrate how witty and sarcastic Jane Austen can be.

“I do not want people to be very agreeable, as it saves me the trouble of liking them a great deal.” —personal correspondence “The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, must be intolerably stupid.” —Northanger Abbey “Silly things do cease to be silly if they are done by sensible people in an impudent way.” —Emma “Next to being married, a girl likes to be crossed a little in love now and then. It is something to think of, and it gives her a sort of distinction among her companions.” —Pride and Prejudice “Nothing ever fatigues me, but doing what I do not like.” —personal correspondence “A woman, especially if she have the misfortune of knowing anything, should conceal it as well as she can.” —personal correspondence “Stupid men are the only ones worth knowing after all.” —personal correspondence “Selfishness must always be forgiven, you know, because there is no hope of a cure.” —Mansfield Park

I haven’t done half as well as I’d hoped at conveying how hilarious Austen really is, but time and word limits won’t allow me to elaborate further. Every novel has at least one character who is a walking joke. Trust me: ease yourself in with Lady Susan and you’ll see. In the meantime, if you want more Jane Austen, check out our Jane Austen Archives.