Gifted and cursed with the ability to see the future, Mildred Groves takes a position at the Hanford Research Center in the early 1940s. Hanford tests and manufactures a mysterious product to aid the war effort. Only the top officials know that this product is processed plutonium, to make the first atomic bombs. Inspired by the classic Greek myth, this 20th-century reimagining is based on a real WWII compound. A timely novel about patriarchy and militancy, The Cassandra uses both legend and history to examine man’s capacity for destruction, and the compassion it takes to challenge the powerful. I’ve never left my princess phase. While reality has grounded some of the more glamorous aspects, a part of me enjoys the fantasy aspect that the Disney movies cover, or the idea that you are viewed as someone special. Who doesn’t love the outfits, or the songs, or the dancing? Of course, real life wasn’t like that. Being a princess or any form of royalty comes with a price, the burden of responsibility. More than one person wants the title, and all that comes with it. If you wear the crown for one day, you may lose your head in a few months, as Lady Jane Grey could tell you. If you belonged to the Austro-Hungary royalty, dating the wrong lady from the tennis court could mean you have to cede your right to inherit if you want to marry her. We want to believe in the ideal of a royal who wears the crown and views it as a burden, that takes the responsibility with the balls and the dresses. And our fiction sometimes represents that when we dive into the real-life royals, especially regarding children’s literature. In this article, I’m going to discuss some of the historical fiction that goes hand-in-hand with portrayal of royalty in middle grade and YA literature. My primary source of reference for children’s literature comes from Carolyn Meyer’s Royal Diaries and Young Royals series. These take a literary democracy, in that each story has a perspective from a royal.

Empathy for the Dead

Fiction is all about making us understand other perspectives, and creating a democracy where multiple characters can tell their story. Professor Azar Nafisi covers this in Reading Lolita in Tehran, albeit by discussing Nabokov’s books. Vladimir Nabokov came from a noble family that could trace roots back to a Russian prince; they had to flee before the 1917 February Revolution could depose them. They had a narrow escape; the Romanovs—including the Tsar Nicholas II and his family, which included four daughters and one son—would later die in 1918, executed in a basement. Later, because Duchess Maria’s body was missing, rumors spread that the girls may have survived by sewing jewels into their dresses. A woman named Anna Anderson gained notoriety by claiming to be the Duchess Anastasia, and managed to convince several relatives.

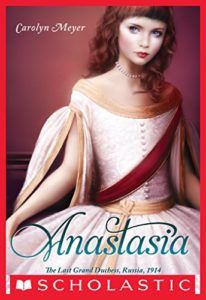

We wanted to believe that Anastasia had survived, at least in the United States; Russia seemed to believe that Maria was the survivor. Heck, my generation received an animated movie based on that premise, an ice show, and a direct-to-video sequel; we also got a Broadway play two decades later. The material does gloss over the fact that Tsar Nicholas II was a terrible ruler, including how he handled Russian’s involvement in World War I, but it’s understandable considering that the government that followed seemed to celebrate that they had murdered children. Sadly, in 2007, DNA tests did confirm that Anastasia died with her siblings that night. Why did we hope for this impossible dream? Was it because, compared to her father, Anastasia and her siblings were innocent? None of them except Alexei would have inherited the Russian throne and her problems, and Alexei, the oldest, was a teenager. The government in charge found reason to burn some of the bodies and hide them, which does not imply that the public would celebrate. Then we get to the issue of how we portray the Romanovs in fiction. In Anastasia: The Last Grand Duchess, Russia, 1914, Carolyn Meyer takes a sympathetic approach. Anastasia in her diary talks about how her sisters argue about if “figure” or “bosom” is a more appropriate term for their growing bodies, about how much butter they get on Easter, and on how Father Grigory heals their little brother. We find out in the afterword that the lifestyle was excessive when most people were starving in Russia. Even so, the execution was disproportionate. Obviously, we should celebrate fiction because it can show us these perspectives. When we close our eyes and ears to empathy, then we lose that part of humanity that can redeem our flaws. At the same time, we cannot ignore the consequences that the living and the dead suffered. Books allow us to view both the empathy and the consequences.

Flawed Historical Figures

We have problematic royals, in history and in our present. Some are not the glossy fairytales that we adored as kids, rendered in hand-drawn illustrations and getting dog-eared. Quite a few made costly tactical errors that led to many deaths, or worse. Mary Tudor is a classic example of a problematic royal; she has the moniker “Bloody Mary” for a reason. After she took the throne, she deposed and executed her cousin Lady Jane Grey who had been given the crown. More executions followed, due to her undoing her father’s foundation of the Church of England, sanctifying the marriage between Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon, and enforcing a Catholic doctrine. Hundreds burned at the stake. Others chose exile. In Carolyn Meyer’s Young Royals series, she portrays Mary Tudor as someone who could conceivably become the queen known as “Bloody Mary” after a childhood where her father, formerly spoiling her rotten and loving her, became a completely different person and treated her as nothing. Mary, Bloody Mary establishes the norms and identity that this Tudor had, and how the changing status quo changed her as well. The afterword points out that while Mary conducted a religious purge, which included mass executions of Protestants, she wasn’t that different from her father, who drew and quartered Thomas More, or other similarly murderous queens. Later Young Royals books would show the perspectives of Elizabeth Tudor, Anne Boleyn, and Catherine of Aragon. Each woman thinks they are doing the right thing and what’s best for themselves and their country. The afterwords ground us by showing the consequences and values for the time.

What it Means for the Future

Soon those in our present will become historical figures. Right now, at least in the States, we are deciding who will go down in history as the worst or the best, depending on where we stand at this point in time. I wonder how we got to this place, and what happened to the beliefs that we had before. The royal politicians of the past can help us figure out how to process our grief, denial, and sense of loss. Perhaps a book about the royals in Saudi Arabia will help us understand the senseless execution of a journalist, while never condoning it. Maybe we can understand the politics that go into decadence, and the love that accompanies the pain. Let’s draw inspiration from historical fiction to ground our royalty fantasies.