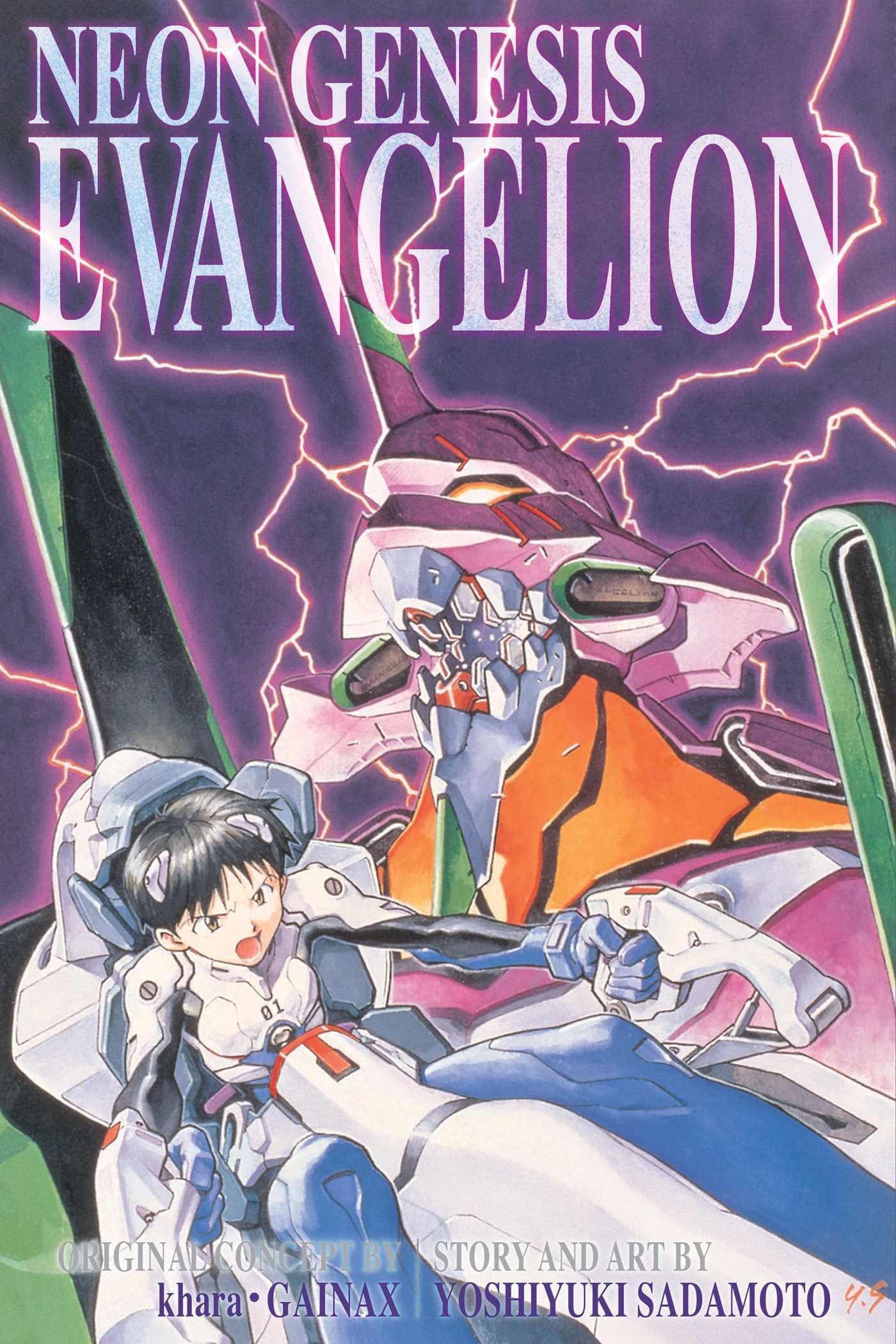

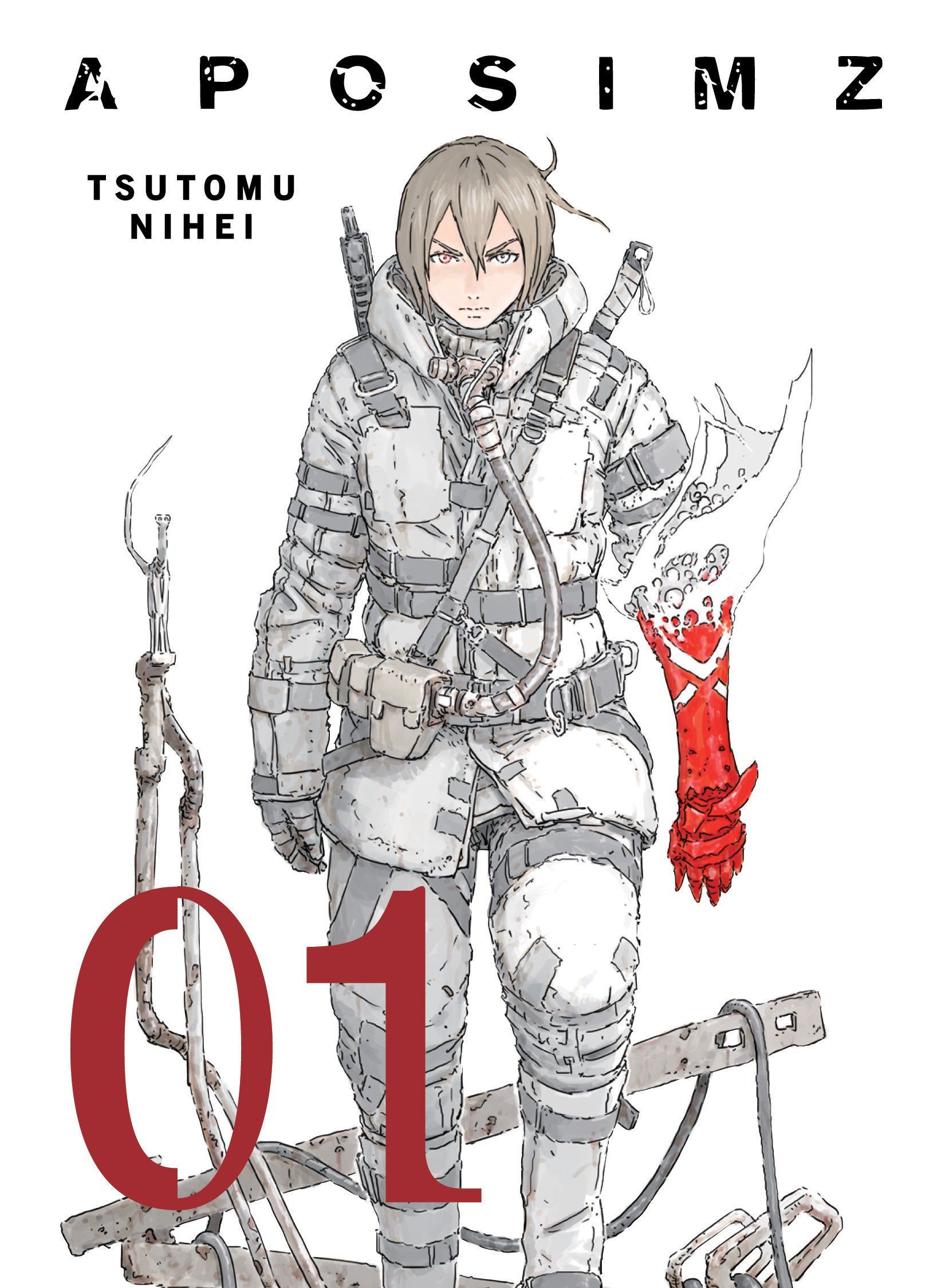

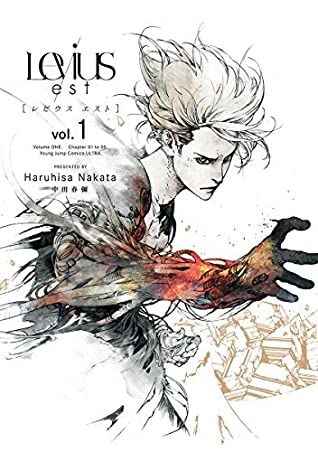

It is no secret, and should come as no surprise, that fiction about robots is full of conversations about industry, humanity, and how the organic self is perhaps forced to blend with the artificial; either to its own detriment, maybe in the name of progress, or simply as a way of reconciling feelings on authenticity in the contemporary industrial age. The themes of self and other, of person vs machine, are engaging and thoughtful – even moreso in our current times. Reading mecha manga while stuck in my house, refreshing emails and news outlet apps in the hope of catching restriction updates, I couldn’t help but feel like it became a conduit for my weighty thoughts on how the ongoing pandemic was on the crux of changing yet again, especially as returning to work and ‘normal life’ became a more realistic possibility. Even though I succeeded in my goal of finding relatable robot literature, I was left rattled, increasingly stressed and concerned about what awaits in the future, and acutely aware of how my human identity has been transformed by the pressing force of capitalist expectations. Enjoyable and exciting on one hand, acutely personal on the other, mecha manga allows for the exploration of what happens when a person slips beyond the boundary of typical human life and crosses into the mechanical, the trials and tribulations of finding yourself in high stakes, perhaps alienating circumstances, where the fate of everything hangs on you getting back in that big robot. But is that really a fantasy? Isn’t that something I do every day? The volumes discussed in this article are all written by men, as, much to my surprise, I struggled to find mecha stories by a women mangaka, both commercial or indie. Hiromu Arakawa’s Fullmetal Alchemist comes to mind as a parallel to Levius/Est, as it prominently features automail, in the same way that Levius features mechanical body augmentations, and I would also be interested in a discussion about whether or not her protagonist Alphonse counts as a mech… Before picking this volume up, I’d heard that people had difficulty with Shinji as a protagonist, calling him frustrating and whiny as he constantly hesitates and doubts his loyalties to Nerv, the company working on the EVA program. By contrast, Shinji’s struggles and apprehension strongly resonated with me. I, too, wouldn’t want to get into the amniotic mech to punch aliens. I, too, don’t want to be part of the machine set up by a rather anonymous force who only value your ability to follow commands for a bare reward and dangle the idea of responsibility to humanity over my head. Shinji’s dilemmas throughout Evangelion distinctly remind me of the conversations I’ve had with myself and friends about the demands of capitalism, even during a worldwide catastrophe; furiously lamenting about how we’re meant to carry on with these draining, horrific tasks for little recognition, how we are ‘essential’ to keeping the world turning, despite ongoing tragedy, but how we see no direct benefits of the effort we supply. Likewise, Shinji saves Tokyo over and over, but the mere survival of his home, just to keep existing in it, is still hardly enough of a reward to encourage him to continue, to block out thoughts of despair. Evangelion is pensive, asking: how do you stay motivated, how do you steel yourself to get back into the robot, get back in the game, when you are valued not for your humanity but for your ability to do an industrial task? And, if there is truly no way to resist it, for fear of obliteration or just letting people down, how do we manage to find solace and appreciation to keep us afloat when the big robot inevitably collapses in on us? It represents, to me, one of the best reflections of our current predicament and how it has changed our mental health. This blending of the robotic with the organic in Aposimz, the forced assimilation of the self with the pre-programmed, struck me as a unique metaphor for the ways in which we have to ‘keep going’ through trialing times, no matter our personal opinion on the situation, if only to see it through out of spite. Just as this protagonist does not necessarily want to become one with the robotic parts of himself, merging with the machine (representative here of capitalism) becomes his only option. Nearly killed by a cyborg abusing his powers, the protagonist has to rely on the same violent systems to continue living and eventually destroy the one who forced him to make this literally dehumanising choice. The dream of punching capitalism in the face with a super-sonic robot canon attached to my arm is real. Where one of Shinji’s characteristics is his reluctance and resistance, Etherow’s defiant use of a futuristic code, to become a Regular Frame cyborg and become motivated to take down the culprit of his misery, makes this manga a compelling story that resonates with the complex decisions and sacrifices we have to make in the contemporary world regarding work and autonomy. Once again, I came away from this story thinking that it wasn’t necessarily a fantasy, but an allegory for contemporary industry in sick, decaying times. Aposimz emerged from my pandemic reading as an appropriate study of how we can be forced into involuntarily succumbing to the pressure of the workplace in extreme circumstances, but how we hope that what we gain from it may keep us surviving, hope that we can somehow manipulate the system for ourselves. We may not have the ability to transform into skeletal robots, but who among us hasn’t transformed into our ‘worksona’ just to survive a long shift, crossing our fingers that if we use the tools of capitalism, maybe we’ll get a bigger tip and it’ll all be okay? Like Aposimz, the success of such a method of coping seems overwhelmingly bleak. Rounding out the cast is AJ, a girl who is recovering from being the preprogrammed drone of a violent organization, whose memories of her brutal acts, as dictated by her controllers, have been removed as a means of protecting her and allowing her to reconnect with her human identity. In a world in which we may feel puppeteered by faceless and greedy corporations, this subplot of Levius/Est especially struck me as a meaningful reflection on the ways in which it can be difficult to find oneself again once we have been disconnected from capital; when everything closed in 2020 and I – as well as countless others – lost my job, it was strange to suddenly be without a schedule, without a daily purpose to get out of bed. We may strongly dislike the conditions we work in, feel unfulfilled in our positions, but when it’s ripped out from under us, the odd process of healing and rediscovery of who we are, without work, can be an awkward stumble into the unknown. As AJ learns to no longer be a machine, as her body and consciousness are her own again and no longer piloted by another, she represents an inversion of the mecha genre – we get, here, a perspective of the mech itself. As the pandemic removed work from our lives and we had to learn to inhabit ourselves again, no longer piloted by the expectations of daily labour, management orders, or company statistics, I find AJ’s similar journey towards self-possession relatable and intriguing. However, when it came to locating manga about people getting inside large robots, as in Evangelion, I found the field dominated by writers and illustrators at least using male pseudonyms. I refuse to believe that mecha manga by women doesn’t exist at all (therefore, please send me recommendations!). If we are to read mecha manga through the lens of capitalist critique, then I can imagine a robot story that reflects how women are treated in the workplace would be extremely interesting and subversive. I find myself thinking about PK Page’s poem ‘The Typists’ or Yun Ko-eun’s The Disaster Tourist, both of which discuss the pressures of capitalism and how women succumb to autopilot, to automation, to navigate misogyny and despair in their workplaces: could these be considered mecha stories? The pandemic transformed science fiction into mundane reality. Reading tales of autonomy and the struggle to survive within new structures – whether that’s the metaphorical ‘structure’ of society, or the literal mechanical framework of a giant robot – has been somewhat of a comfort, but also a cold bucket of water to the face as I process my feelings about work, labour, and being as lockdown eases. I have seen plenty of memes and jokes online about how the mecha genre has its potential overlooked, and how reducing it to ‘big robot smackdown’ dilutes the sociopolitical, anti-war, anti-capitalist interpretations, and exploring these manga for myself has been undeniably transformative. I don’t want to get back in the robot either, Shinji, but it’s waiting for me all the same.

Further Reading

Curious to know how COVID influenced our reading in other ways? Check out this article on how realistic fiction became fantasy fiction for one Rioter. Or, to find more books about robots and AI to trigger an existential crisis, click here!