But what is the story behind this legendary cookbook, still publishing 85 years after its first edition? Why does it endure and why has it become a staple of American cooking history? Let’s get to know a bit more about the history of Irma Rombauer’s (The) Joy of Cooking, which has sold over 18 million copies.

The Birth of The Joy of Cooking

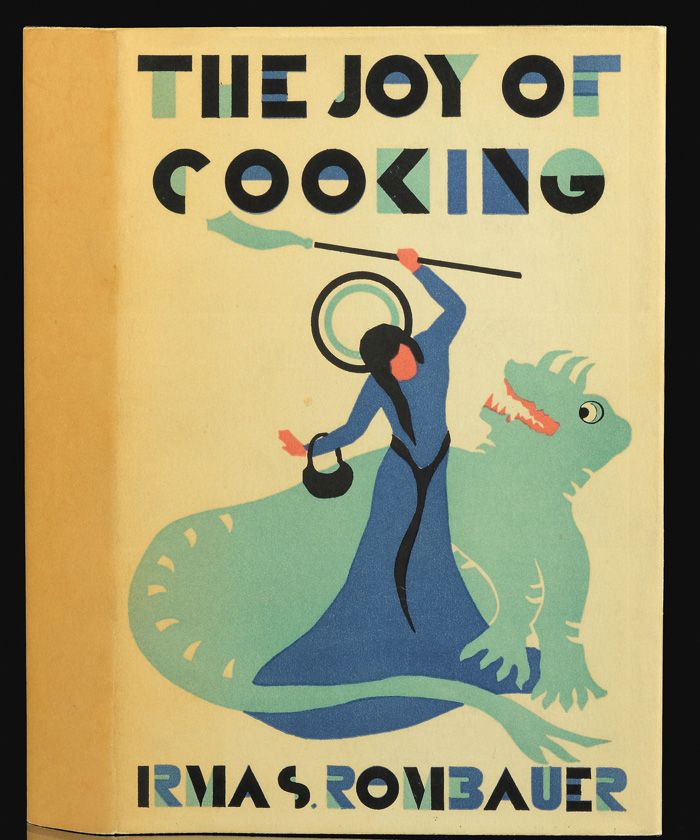

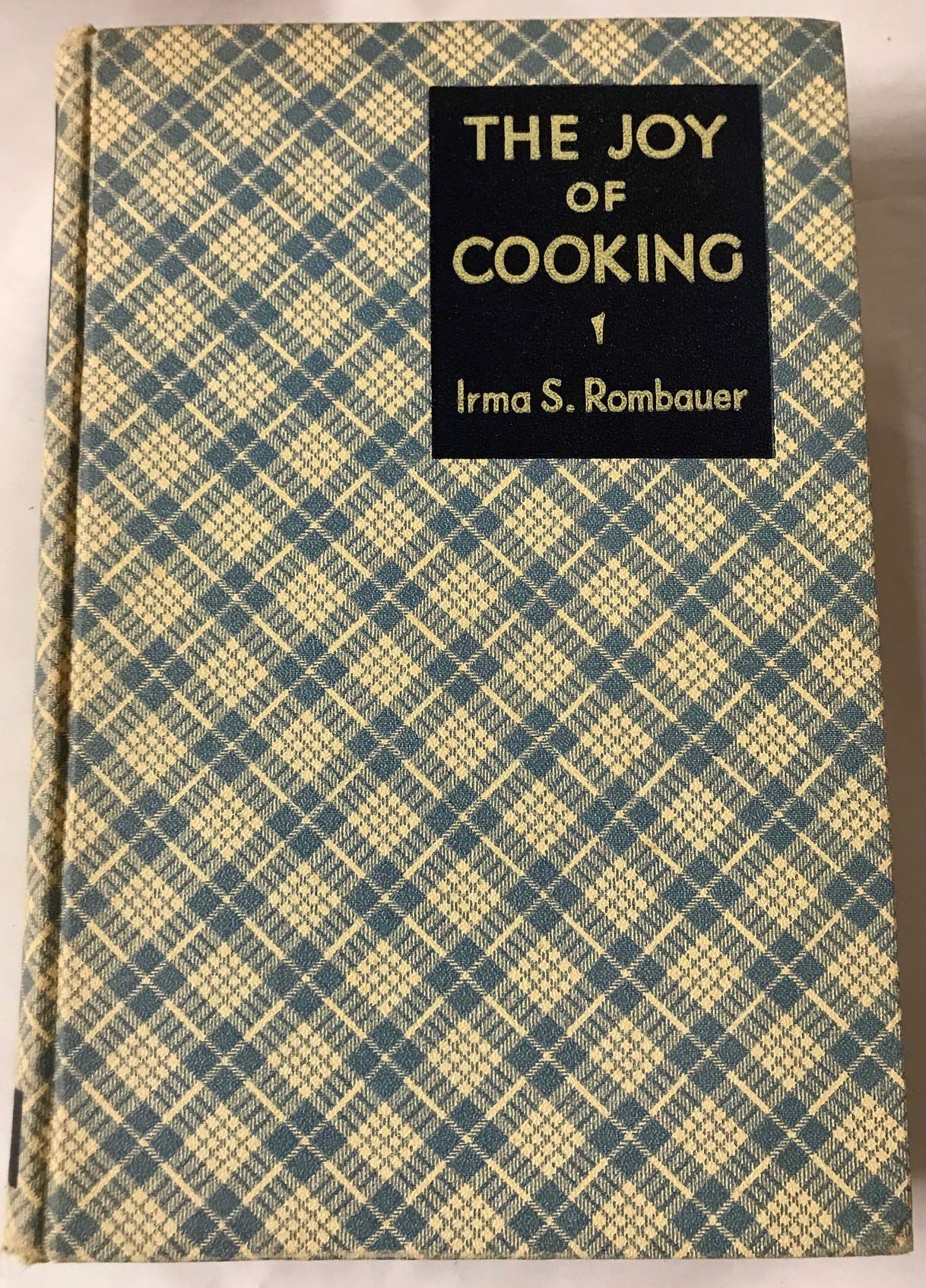

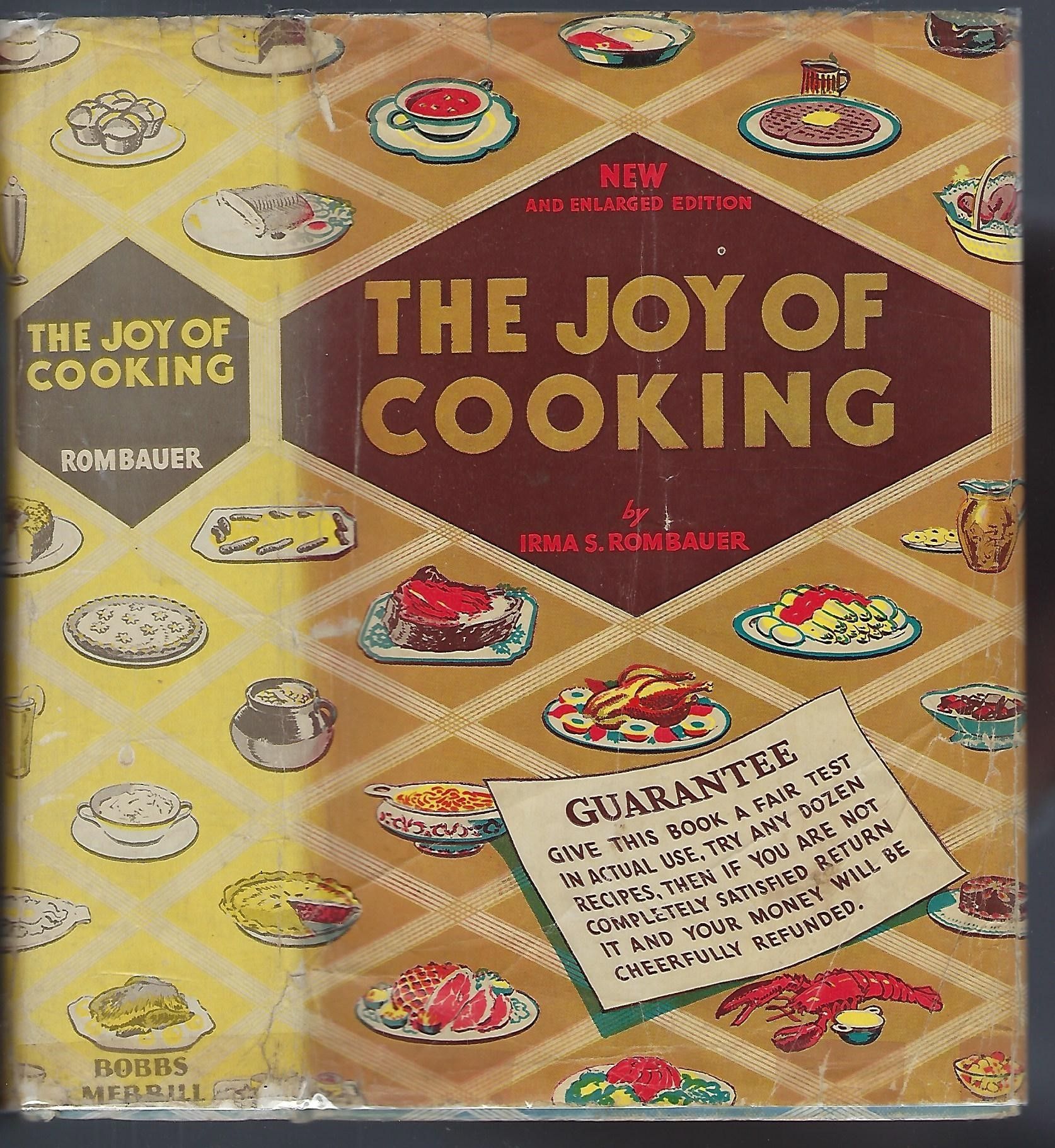

Born to German immigrants of wealth in 1877, Irma Rombauer found herself shuttling between Saint Louis, Missouri, and Bremen, Germany, throughout her teenage years. Though not trained formally in cooking, Irma’s daughter Marion — who is co-credited on Joy of Cooking — credited this exposure to European cuisine in Irma’s young years to her learning the skills necessary to not only feed her household, but to develop creativity and confidence in the kitchen. “It is true that a few of Mother’s culinary beginnings were on the conventional side. One such was the casual introduction during her formative years to a varied European cuisine,” wrote Marion in her mother’s biography Little Acorn: The Story Behind Joy of Cooking, who added that the her mother lucked out to experience more “formal” classes during summer vacations to Bay City, Michigan. “This acquaintanceship formed a subliminal foundation of sorts when she attended a series of seasonal cooking sessions presided over by a Mrs. Ray Johnson of Paris, Kentucky, who spent her summers, as did our family, in Bay View, Michigan. The date must have been around 1915. The Johnson ‘School’ was perhaps Mother’s only exposure to formal culinary training. But it brought out in her an unusual and at first rather inexplicable flair for decorating cakes.” Despite having experienced international cuisine, travel, and formally informal classes, Irma never quite saw herself as a cook. In Joy of Cooking, she writes about those formative days in her marriage wherein she “was once as ignorant, helpless and awkward a bride as was ever foisted on an impecunious young lawyer? Together we placed many a burnt offering upon the altar of matrimony.” Irma instead saw herself as an impeccable hostess. She loved to host gatherings, both those which had time for planning, as well as those which were more spur of the moment. Her husband Edgar, who she married in 1899, was a lawyer and would frequently invite over guests, including those in the St. Louis Urban League and City Hall. Irma herself was involved in the community and hosted numerous gatherings, especially musical ones during her time on the board of the city’s Symphony. “Most of these visitors were European. Virtually all had few close friends in the city, were not averse to an informal home-cooked meal, and enjoyed a quiet encounter with sympathetic people who could in some instances literally speak their language — or, rather, one of their languages,” wrote Marion, who, in the biography of her mother, highlighted the gayety of these events. One of the guests, “especially delighted the company with his parodies of nineteenth-century bravura pieces, executed with the dramatic help of a large navel orange, which he rolled sonorously over the keyboard.” Throughout the early 1920s, Irma had been sharing recipes with her beloved Women’s Alliance. She’d been asked to hold a class with the Unitarian church, and had pulled together around 73 recipes in those years to help make the classes possible. Everything was working out well for the well-born, well-bred Irma, who loved hosting and celebrating. But then, in 1930, her husband Edgar died by suicide after a long bout with depression —something that, in later stories of his family, would seem to have been a mental illness with which his father also struggled. Following Edgar’s death, Marion and her brother urged Irma to channel her knowledge of food and entertaining into something that would reach beyond their community. It’d help her find bigger purpose and share her talents in a much bigger way. Marion and Put — the nickname for Edgar Junior — were both adults and preparing to leave home, when it became clear their mother’s newfound widowhood would fundamentally change her life and security. “It was at this juncture, partly to comply, chiefly to distract her keen unhappiness, that she decided to spend another summer in Michigan, taking with her, needless to say, the mimeographed sheaf of recipes she had compiled, some eight years before, for the Women’s Alliance. She knew she needed salvation in work, and that to work she must manage to avoid people, much as she loved and attracted them,” wrote Marion. She added, “[Irma] had no inkling, of course, that she was carrying with her into Johnny Appleseed country an acorn of even more promising potential, or what world-wide companionship its growth would bring her, what years of absorbing activity.” In the years that followed, Irma sought the help of a family friend to type out and critique her recipe pages. Irma then forwarded pages regularly to Marion, who now lived in New York City with her husband. There, Marion would test recipes for her husband John, his sister, and her fiancé. Marion moved back to St. Louis, working as an art director. On weekends, she created chapter headings and production of what would become Joy of Cooking. “How naive and straightforward was our approach to publishing!” recalled Marion. “We simply called in a printer. I remember the Saturday morning he arrived, laden with washable cover fabrics, type and paper samples. In a few hours all decisions were made, and shortly afterwards we signed a contract for 3,000 copies complete with mailing cartons and individualized stickers. Then came the new experience of galleys, proofreading and preparing an index.” Joy of Cooking was published in 1931 when Irma was over 50 years old, and she spent $3000 of her own money to print the book. It had over 500 recipes, and it was conscious of the reality facing the country: The Great Depression. The cookbook posited that “inexperienced cooks cannot fail to make successful soufflés, pies, cakes, soups, gravies, if they follow the clear instructions given on these subjects. The Zeitgeist [The Great Depression] is reflected in the chapter on Leftovers and in many practical suggestions.” Also included in the 1931 edition were silhouette drawings by Marion. The book sold well among Irma’s friends, with 2,000 of the privately printed 3,000 copies reaching the hands of eager readers and home cooks. Irma was satisfied — but not enough. She wanted more for Joy of Cooking and sought a bigger operation for the book’s publishing, eventually landing with Bobbs-Merrill. The president of the publisher had met Irma while she visited her cousins in Indianapolis, and he had always been a fan of her cooking. Now, Joy of Cooking would see full-fledged publication in 1936. It would be much more expansive. Where the 1931 edition had 396 pages, the new edition boasted 640. “Although I have been modernized by life and my children, my roots are Victorian. This book reflects my life. It was once merely a private record of what the family wanted, of what friends recommended and of dishes made familiar by foreign travel and given an acceptable Americanization. In the course of time there have been added to the rather weighty stand-by of my youth the ever-increasing lighter culinary touches of the day. So the record, which to begin with was a collection such as every kitchen-minded woman possesses, has grown in breadth and bulk until it now covers a wide range,” reads the introduction to the 1936 edition. This conversational tone is what made the book appeal to readers, who could both see themselves — and see their aspirational selves — in the pages of Joy of Cooking. Irma’s tone is frank, admitting to readers, as much as to herself, that she’s not a professional and has found herself with too little time or expertise to create ideal meals. The goal was to be a book usable to the average person, and readers were captivated both by the book’s banter and its own claim to be the cookbook of record.

The Joy of Cooking Comes of Age in America

What made Joy of Cooking really catch on was its timing — luck in an era of deep loss and struggle. Many homes were letting go of home cooks, chefs, and other hired help, and those in the household were now finding themselves responsible for tasks like dinner, which they’d never had to attempt by themselves.

It was not, however, all gravy for Irma. When Bobbs-Merrill took over publication of the cookbook, they retained not only the copyright for the 1936 edition, but for the original 1931 as well. This meant they were able to cash in big time. The well-selling book went on to be a far bigger success for the publisher than it was for Irma and her family, and the long copyright battle, which highlighted the realities of the publishing world in this decade, is explored in the book Stand Facing The Stove.

The 1936 edition of Joy had a 10,000 copy first printing, and between its initial publication and 1941 sold over 52,000 copies.

Irma was eventually able to regain copyright of her work, which empowered her to have more editorial control of Joy of Cooking, and, most important for the book’s long legacy, name the successors for the book’s writing. She also published two other cookbooks at the time, Streamlined Cooking and A Cookbook for Girls and Boys. Neither did quite the sales nor maintained their status as a staple as Joy.

Unlike other cookbooks of the time, as well as cookbooks and recipes we’re more familiar with now, Irma’s Joy of Cooking did not use the standard format. Ingredients were not listed separately, but instead, the recipe was laid out in a narrative, step by step through the process, with ingredients named in bold as they arose. The recipes also included baking times, size of pans needed, new methods for cooking meat, and it included recipes for leftovers and use of pre-made, canned products where appropriate.

A new edition of Joy came in 1943. It, too, was expanded from the prior edition, weighing in at 884 pages. The new edition incorporated many of the recipes from Irma’s Streamlined Cooking — recipes that could be made in 30 minutes or less, using primarily frozen or canned ingredients — and spoke to readers with the knowledge of the reality of wartime rationing.

The book sold phenomenally well. Almost 170,000 copies moved in 1944, roughly 100,000 in 1945, and almost 300,000 in 1946. Though the book was still published by Bobbs-Merrill, paper rationing from the war had an impact, and some of the 1945 and 1946 editions were published by Blakiston Company of Philadelphia. Interestingly, as the sales numbers reflect, there was an uptick in interest after the war, and sections on wartime rationing were removed in 1946. They were replaced with 40 more pages at the end of the book from Streamlined Cooking.

Big changes happened for the book in its next edition, 1951. Irma was still alive but in ailing health, and her daughter Marion took a stronger role in the book’s content and design. She’d been named successor in the earlier negotiations between her mother and the publisher.

Marion’s name graces the cover of the 1951 edition, and she fought hard with the publisher to ensure that the book wouldn’t include pictures to illustrate recipes. She sought out her friend, Ginnie Hofmann, to include illustrative drawings in the style of the previous editions instead.

In collector’s circles, as well as in cookbook history, the 1951 edition is often seen as the messiest one made. It was put together quickly, with legal battles between the family and publisher taking priority over things like copy editing and design. Both Marion and Irma saw the index in particular to be “deficient.” But Marion’s vision for this edition stayed true to her mother’s: it was conscious of the times, and it brought with it recipes that included modern tools like blenders, more recipes that were conscious of whole grains and fresh produce, and it removed many of the previously-included Streamlined Cooking recipes which relied on canned goods. This is evident of the changing times and rising (white) middle class of the times.

The 1951 edition had a 100,000 copy first printing, with subsequent printings in 1952 and 1953 to clear up the errors. Each of these editions eclipsed 1,000 pages, and the 1952 edition sold upwards of 202,000 copies.

The subsequent edition of Joy was published without Marion’s editorial consent in 1962, the year Irma died. In 1963 and 1964, Marion made corrections to the ’62 edition and insisted the publisher exchange the copies released without her permission with them. This was the first edition published in paperback and made available as a two-volume set in that format. It rang in at over 860 pages, a limitation placed on the book by the publisher.

Many consider this 1962 the unauthorized edition and valueless — it’s riddled with errors, and isn’t friendly for home cooks. Marion allegedly discovered the printing without her permission while attending her mother’s wake, though she didn’t acknowledge it widely.

All three of the Joy editions in the 1960s sold similar quantities as prior years. In 1973, the paperback was made into a trade format, single volume, and circulated into the 1990s.

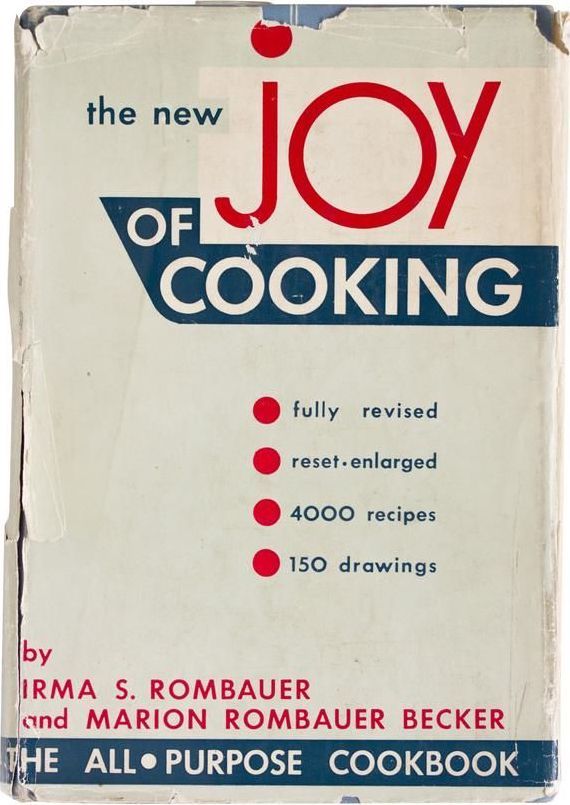

It’s the 1973 edition that most readers are likely familiar with, and it was the last Joy of Cooking edited by Marion. The 1000+ page tome included not just over 4300 recipes, but sections on hiking and backpacking, as well as recipe substitutions. It was the longest running edition and many believe it most true to how Marion envisioned the book to look and feel, upholding both Joy‘s legacy and future. It sold over 6 million copies and stayed in print and unchanged for 20 years.

The family legacy didn’t stop, though, even with the complete overhaul of Joy of Cooking in 1997. Ethan Becker, Marion’s son, edited the volume; his training at Le Cordon Bleu helped him shape the book’s new recipe look, with a focus and emphasis on freshness and convenience, as well as deep descriptions of ingredients. The publishing of this edition, both because of Ethan’s role, its cultural moment, and the history of publishing, eliminated one of the features which made the book so valuable to readers: the conversational tone.

The Joy of Cooking was no longer a book by amateur home cooks. It now had a culinary pedigree, though throughout the subsequent years, facsimiles and reprint editions have worked to honor or revisit what made Joy such a gift. The 2006 75th anniversary edition was based on the book’s most popular 1973 edition and remains popular and beloved today.

Both the 1997 and 2006 editions have over 1500 pages.

One more recent edition, published in 2019, included 600 new recipes, and it was edited and updated by Irma’s great-grandson John and his wife, Megan.

The Joy of Cooking in Contemporary Life

The Joy of Cooking remains popular and evokes both nostalgia and the promise of making home cooking accessible to all. Given how the book stayed relevant throughout its 85 year history, and indeed, followed the cultural contours in each of its editions, it’s no surprise that collectors have found true joy in seeking out the earliest volumes. “There are a few notable divisions in edition Joy-ist loyalty. There are the Irma v. Marion camps, for one. When Irma Rombauer fell ill, and then after her death in 1962, Marion Rombauer Becker revised alone, and (among myriad other complaints), some say, just couldn’t replicate her mother’s wit,” writes Genevieve Walker in Bon Appetite. “However, what Rombauer Becker did bring was an attention to detail, interest in whole grains and health foods, and a desire to make the Joy encyclopedic. […] Rombauer Becker wanted it to be a “deserted island cookbook” as her heirs would say — able to address even the possible lack of a butcher.” Collectors love seeking out early editions of Joy, as Walker digs into in her piece. The original 1931 edition at its time, she notes, would likely cost about $2.25. But today, snagging one of those could run anywhere between $1500 and $15,000. Those wanting these books aren’t necessarily going for the recipes, beyond what they said about the times in which they were created — and, in the case of the 1931 edition, the history of self-publishing as a means of developing a literary empire in such an early era. Exploring the cover, typography, and illustrations throughout the history of Joy also bring delight. As Mental Floss highlights, Marion was a forerunner for design, using a simple, lowercase choice for the title font in 1951. This would become a common style choice in the following decades for other cookbooks. Is it The Joy of Cooking or Joy of Cooking is one of the long-time questions readers have wondered, and the answer emerges with the help of the unauthorized 1962 edition. With the publication of paperback, as well as changes needed to be made to Marion’s standards, the “The” was dropped from the title. Before that, the book was The Joy of Cooking. Many still use Joy for home cooking, of course, including those who see the 1973 edition to be the definitive, most realized version in its 85 years.

Tidbits to Chew On

Prior to marrying Edgar, Irma had a whirlwind romance with none other than novelist Booth Tarkington, best known for The Magnificent Ambersons. Their romance was epistolary, as Tarkington lived in Indianapolis. Irma and her family had been visiting cousins in the area and they were introduced. Tracking down the information to a clear source has made confirming the rumor that the Vonnegut family was involved challenging, but it’s possible a third literary thread weaves here as well. Irma never had a job, as she grew up wealthy and maintained that wealth. Her father, as well as Edgar’s, were both German Americans who believed in ending slavery and women’s suffrage. Irma, as noted above, was widely involved in community and cultural affairs throughout St. Louis, and, according to Literary St. Louis: A Guide, she and friend Edna Fischel Gellhorn set up a clinic that helped sex workers by testing for and treating venereal disease. As for the book’s history and legendary status both in the kitchen as as a work of literature, Julia Child noted the 1943 edition of Joy as her very first cookbook. She called it a “fundamental resource for any American cook.” Can a cookbook be literature? Of course, and if any cookbook could attain that status, no doubt Joy of Cooking is among them, with its rich history and tapestry of recipes, wisdom, and insight. Despite its creation by a wealthy white woman, the approachability and sensibilities to the middle classes makes it a tome worth exploring as a work of literary history and merit.